FX Beauties Comment, Artemis Papachristou, 2019

FX Beauties Comment, Artemis Papachristou, 2019

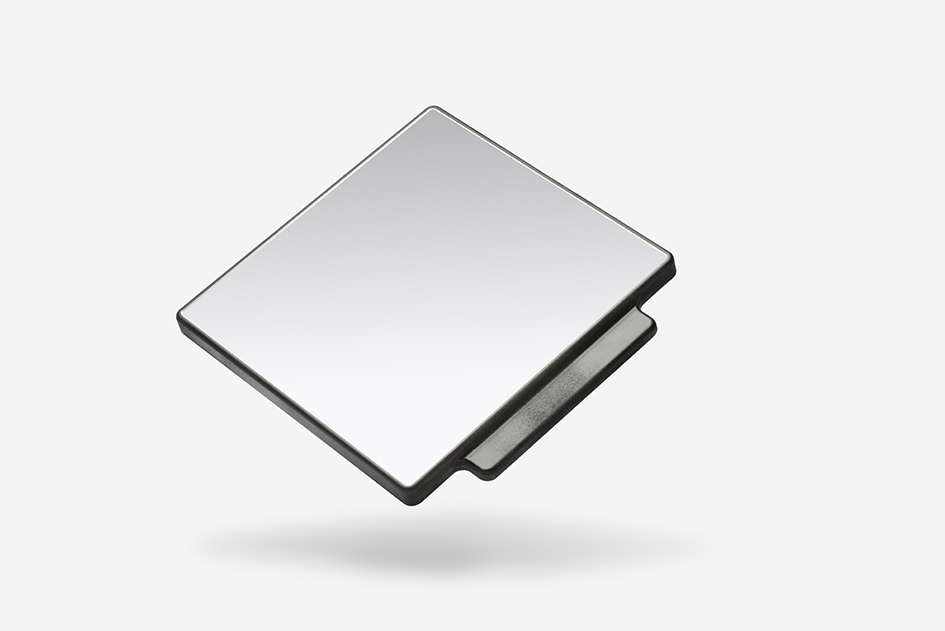

The FX Beauties Hand Mirror 03, Photo by David Stjernholm, 2018

The FX Beauties Hand Mirror 03, Photo by David Stjernholm, 2018

The birth of Japan with the Sun Goddess, 1856

The birth of Japan with the Sun Goddess, 1856

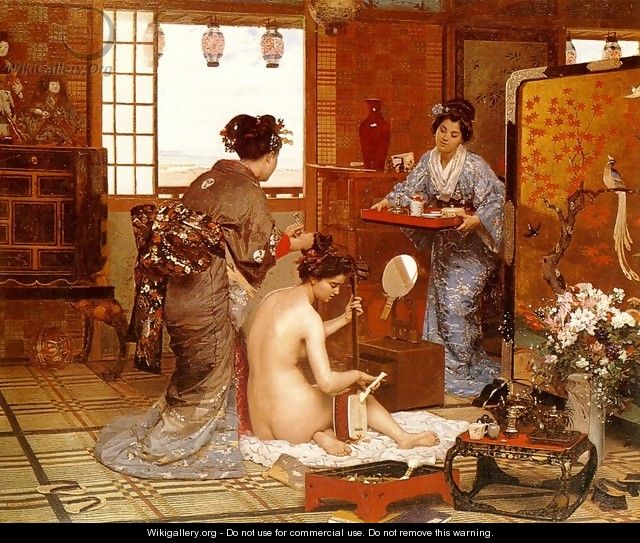

Marie-Francois Firmin-Girard, The Japanese Toilette, 1873

Marie-Francois Firmin-Girard, The Japanese Toilette, 1873

The FX Beauties Hand Mirror 02, Photo by David Stjernholm, 2018

The FX Beauties Hand Mirror 02, Photo by David Stjernholm, 2018

The FX Beauties Hand Mirror 01, Photo by David Stjernholm, 2018

The FX Beauties Hand Mirror 01, Photo by David Stjernholm, 2018

From a one dollar everyday item in a convenience store, to a holy object at an ancient shrine, the mirror is one of the most diverse cultural objects embedded within financial interpretations. To most, the mirror is used as a tool for personal care and is an essential part of our everyday lives. Described by sociologist and design theorist Benjamin Bratton, amongst others, mirrors are now also the ‘black slabs’ of our modern technological devices that we surround ourselves with.(1)

The contemporary mirrors within our devices have opened up gateways to other worlds. They have also played a key role in enabling one of the largest societal shifts in contemporary Japan where millions of women, mostly housewives, can now empower themselves from within their own homes through engaging with digital financial markets. The black slick-screen of these ‘modern mirrors’ reflects both our connectivity and the production of our individual selves. But what is the future role of these multi-faceted mirrored surfaces beyond technological advancements? Could the mirror, with the ambiguity of its reflections, become a tool for furthering equality?

Around the world, humans have always been searching for their own reflection. From puddles of water to polished stones, we have evolved and constantly re-designed what has since become what we define as a mirror. Whilst the variation of surface, size, thickness, shape and light quality are endless, so too are the meanings. The mirror is a design object that might tell us much more about ourselves than we think.

Mirrors are immensely powerful. Being the only surface that can change the direction of our modern technological weaves — Wi-Fi, the reflective materiality has become a source of domestic infrastructure. The metallic backing of the mirror itself often holds electromagnetic properties that interfere and even block Wi-Fi connections. This force is one that most of us are unaware of when it comes to placing mirrors in our homes and how they can add a layer of protection depending on the placements.

The influential role of the mirror was already recognised in Japan in the 14th century. Japanese court noble and writer Kitabatake Chikafusa wrote in the Jinno Shotoki, that mirrors were seen as a “source of honesty” because they reflect “everything good and bad, right and wrong… without fail.”(2) This existential, phenomenological meaning of the mirror is an essential part of Japanese culture. The country has been said to have been built on the importance of the mirror itself. When the Sun Goddess Amaterasu Omikami was seduced out from her cave with a mirror, the light appeared and Japan was born as a country. Architect and researcher Svend M. Hvass opens his book “Ise - Japan’s Ise Shrines Ancient Yet New“ with this historical myth:

“The Sun Goddess

had been deeply offended

and had hidden herself in a cave.

She refused to come out and the world was thrown into darkness.

The myriads of deities, kami, did not know what to do.

Bewildered, they gathered outside the cave and finally decided

to place a mirror in the branches of a sacred sakaki three.

Hereupon an attractive young goddess performed a dance,

so enticing, so daring,

that the many kami erupted in happy laughter.

The merriment puzzled the Sun Goddess

and she peeped out.

Faced with her own image in the mirror,

she became more curious

and pushed the rock in front of her cave aside just a bit,

the better to see.

A strong kami prevented her from returning to the cave,

and once again, the world was filled with light.“(3)

It is believed that the Sun Goddess resides within the mirror itself called Yata-no-Kagami at the heart of the Grand Ise Shrine in the Mie Prefecture of Japan. Hidden away in the inner temple and forbidden for humans to see—the mirror is truly embedded with mystery. “In the Naiku, or the inner temple, the sacred seat of the Sun Goddess, the ancestress of the Emperor, is preserved the holy of holies, a mirror, emblem of purity and truth, a symbol, too, of the omniscience of the gods, who can divine man’s thoughts from his facial expression.”(4)

Although the mirror is regarded as one of the three most precious artefacts in Japan, the mirror as a cultural and financial object is two-sided. Historically casted in valuable bronze as a symbol of wealth by a Kagami-shi—or a ‘Master of Mirrors’ —these early mirrors were used for burial ceremonies and were embedded with religious weight. Often referred to as the Makyo meaning ‘realm of demons’ in Japanese, they were known as ‘magic mirrors’ since it was possible to hide secret symbols in the layering of the mirror, only becoming visible when a specific beam of light hit the polished metal surface. These bronze mirrors later became an important dowry item for brides of feudal lords. Since then, and especially during the Edo period between 17th until mid 19th century, when Japan was still an almost isolated country to the world, mirrors together with the female presence became an embedded part of the domestic realm.

In Japan, the portrayal of modern Tokyo was anchored in Ukiyo-e meaning ‘pictures of the floating world’ also commonly known as woodblock prints. Often representing geishas and women in their homes, these images depicted their everyday life and household routines. Repeatedly, these women would be reflecting themselves in hand mirrors, sometimes even several mirrors in the same image. Holding a mirror in both hands facing each other, this image creates the illusion of infinitive space filled with possibilities beyond the confines of the home. This intermediate role of the reflective surface became symbolic for the relationship between the woman and the outside world. The specific depiction of women and hand mirrors were even used in Europe where painters would recreate and reflect Japanese scenes, such as by artist Marie-Francois Firmin-Girard in Toilette Japonaise (meaning Japanese bathroom) from the late 19th century.

The reflective surface of the mirror holds the power to suggest other realms and sparks the desire to potentially challenge predefined expectations of a woman in a historically traditional society. The mirror in a contemporary context has maintained the very same cultural and financial value. Enabled by the networked mirror of today in the devices through which we send and receive data, the addition of Wi-Fi engages with digital networks beyond the four walls of the home. This is a radical shift in a country like Japan, where traditionally women are positioned inside the home with the duty as a housewife. After the financial crisis of 2008, the phenomenon of Japanese homemakers engaging with digital currency markets became a fruitful example of how domesticity and global capital intersect through the increasing accessibility of technologies of exchange made possible by these ‘modern mirrors’. This mode of private—although exceedingly powerful—trading is exemplified by The FX Beauties Club, one of the first digital support groups for Japanese housewife currency traders who trade digital currencies in lieu of leaving household savings in the low-interest bank accounts commonly available in Japan.

Traditionally, the role of the housewife excluded earning money and the ability to strive for financial independence. With the Wi-Fi plugged into the walls, women are able to engage with larger markets through the mirrors of their connected devices. At their peak, the trading carried out by the women represents an extensive amount of all retail currency trading out of Japan and it is estimated that there are more than five million members today. The women—although being empowered individually—are a rapidly growing decentralized network challenging the definition of financial identity, gender roles and culture. And this is not only restricted to Japan, but is now occurring at a global scale.

The black screen—the mirror of the modern device—now serves as a facilitator for financial and social shifts inevitably changing a country like Japan and beyond. But what is the role of design in addressing these larger shifts? Can the practice of merging different perceptions of what a mirror is—while respecting cultural differences—become a new tool for creating awareness of equality? Can a new interpretation of the mirror as a miniature world reflective of our common connectivity play a part in addressing these larger societal changes across cultures? Rooted in neither the traditional nor the contemporary, but somewhere in-between.

The text is inspired by the FX Beauties project.

www.thefxbeauties.club

(1) https://strelkamag.com/en/article/koolhaas-and-bratton

(2) Jinnō Shōtōki ("Chronicles of the Authentic Lineages of the Divine Emperors") is a Japanese historical book written by Kitabatake Chikafusa. The work sought both to clarify the genesis and potential consequences of a contemporary crisis in Japanese politics, and to dispel or at least ameliorate the prevailing disorder.

(3) Hvass, Svend M.: “Ise - Japan’s Ise Shrines Ancient Yet New“. (1999). Aristo.

(4) Nohara, Komakichi: “The True Face of Japan“. (1936). p.253