Coffee and conversation street art in northern Yogyakarta. Photo by author.

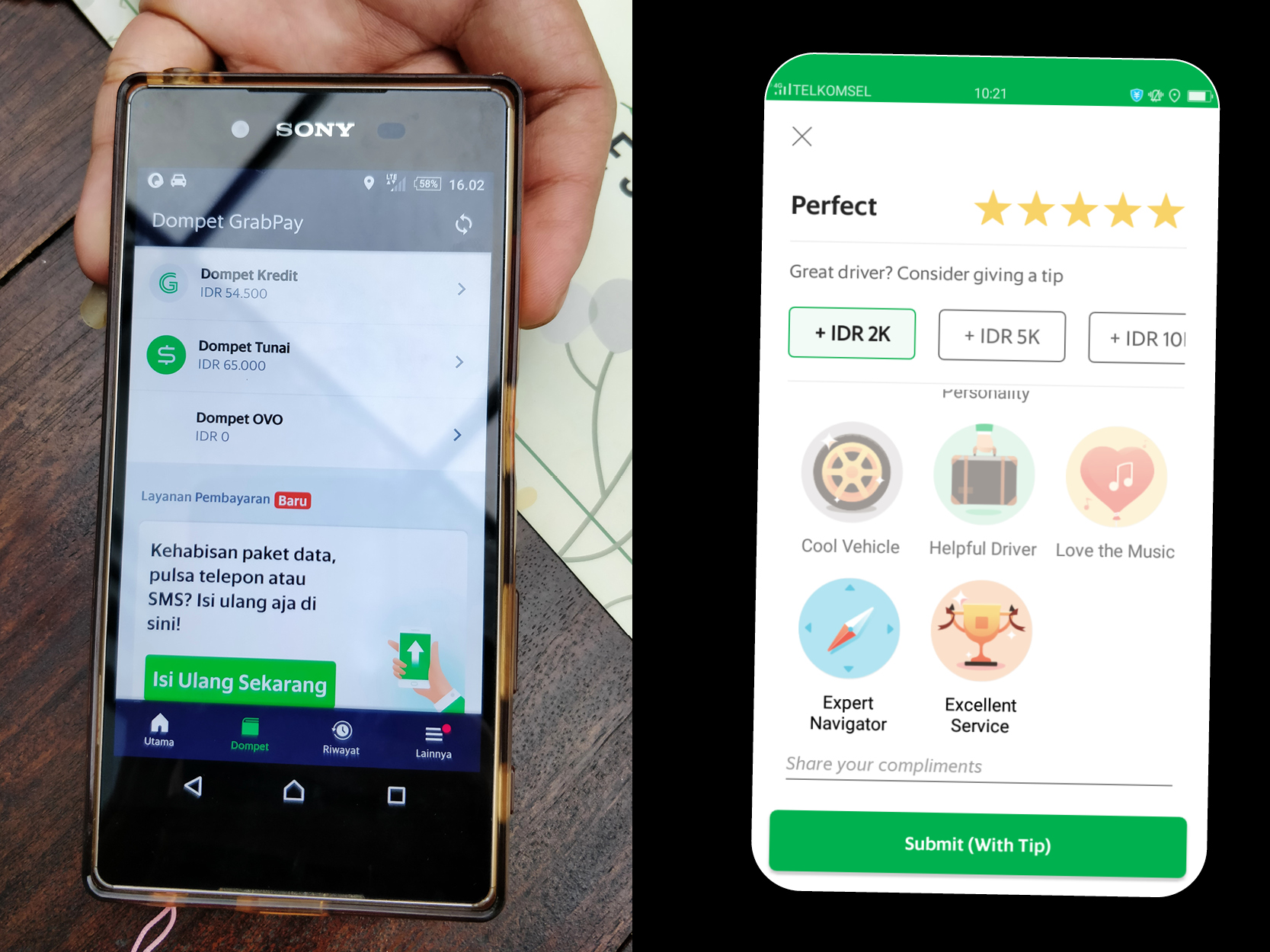

Coffee and conversation street art in northern Yogyakarta. Photo by author. Grab driver shows his credit, cash, and OVO 'wallets' and Grab app driver rating screenshot. Photo and screenshot by author.

Grab driver shows his credit, cash, and OVO 'wallets' and Grab app driver rating screenshot. Photo and screenshot by author.

Photo by author.

Photo by author.

“Belum bisa” the barista told me when I asked if I could pay for my coffee with a digital wallet. You can’t yet. It was one of my first weeks of fieldwork on digital payments in Yogyakarta, and I was confused because I had particularly selected this coffee shop after having seen it listed in the Indonesian Gojek app. I had assumed this would be my first chance to use the apps integrated Go-Pay wallet to make a purchase. The café only accepted cash, the barista explained, but if I wanted to use Go-Pay, there was a way to do so.

I should make an order for my coffee using the Go-Food tab in the Gojek app, selecting the digital payment option upon checkout. A Gojek driver would receive the order, drive to the café, and buy it for me, using cash. The driver would then bring me the coffee and be paid for both coffee related expenses and their time with my Go-Pay wallet balance. It was my first encounter with the entanglements of ‘online drivers’ and digital money in Indonesia, and my first confounding experience of the peculiar limitations and affordances of exchange materialised in the app interfaces.

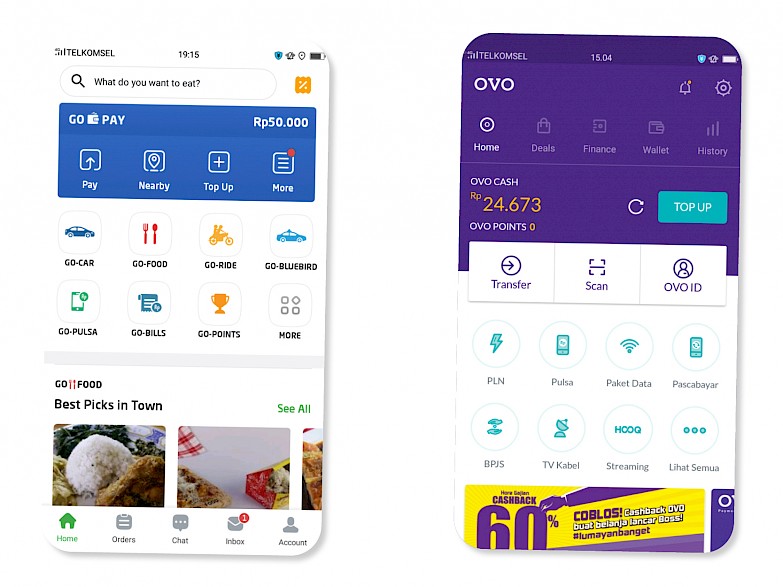

Gojek is an Indonesian app which gives access to a broader ecosystem of services. Initially, the emphasis was on Uber-style transport (Go-Car or Go-Ride), but the app now offers a broad range of services ranging from food delivery (Go-Food) to massage (Go-Massage). Though payments for these services can be made in cash, the integrated wallet (Go-Pay), enables users to pay for all these services “directly” through the app using digital credit. Or, somewhat indirectly, as it were, when trying to buy coffee in early 2018. While Go-Pay is one of the most prominent digital wallets in Indonesia, it is not the only one, with brands such as OVO, and Dana competing fiercely for users.

Gojek and OVO app interface screenshots. Recorded by author.

Gojek and OVO app interface screenshots. Recorded by author.

These “digital wallets” operate as a form of proxy-banking layer for people who might not otherwise have access to making cashless payments. While e-commerce is a booming industry in Indonesia, only a minority of the population use credit or debit cards. Instead, people rely on a myriad of alternatives to facilitate making online purchases, ranging from cash on delivery services to time-limited payment codes that can be used to pay for online shopping with cash at designated agents. Many people are also familiar with prepaid cards issued by commercial banks. Such cards can be used for cashless payment for mall parking, accessing toll-roads, or even vending machine purchases. Thus, the mechanics of the ‘prepaid’ digital wallet apps such as Go-Pay is familiar; they allow users to pre-load accounts by exchanging cash for a digital credit to make cashless payments for things on the go, ‘topping up’ their credit balance as needed through exchange agents.

Notably, like the prepaid cards, once money enters these apps, it only exits again in the form of payments. Unless, for example, you upgrade your account to be a ‘premium user’ to access more features. In other words, though the money stored in my Go-Pay account is denominated in Indonesian rupiah, in practice it operates as a form of private credit. Issued, and stored by Go-Pay it is valid only as payment for Go-Pay services. This type of money sequestration was predicted by sociologist Viviana Zelizer, who researches the earmarking of money; how people, governments and companies designate specific money for specific purposes. In 1996 she wrote “In the future, for instance, e-money may be issued privately by institutions other than banks. Because electronic money is software […] it could be programmed for restricted purposes, to be spent only on designated purchases” (Zelizer, 1996, p. 493). The distinction between cash rupiah and Go-Pay rupiah may seem semantic, but the paradigm shift is noticeable even in the subtle ways that people speak about forms of digital money. For instance, informants would refer to the money stored in their OVO account simply as ‘their OVO’, as if it were its own currency.

In practice, these apps are positioning themselves as alternatives to the publicly available social infrastructure of state-issued currency and cash-based payments. The private, closed nature of an app means it can be difficult as a researcher to access any data about how this affects the storage and transaction of money. Furthermore, though apps may give the illusion of a neat, fixed bit of software, accessible at the tap of a finger, their boundaries and entanglements across devices and third party infrastructure can be challenging to discern (Dieter et al., 2018). In a paper describing methodological challenges and opportunities for qualitative analysis of apps, Light et al. (2018) describe how designers unintentionally leave traces shaped by the cultural, social, political and economic context within which they are created. These are materialised in the interfaces themselves, through available functions, tone, symbolic representations, cumulating in the specific affordances and control mechanisms that users encounter. They draw on the work of S.L. Star (1999) and Brian Pfaffenberger (1992) to develop a method for making visible the underlying infrastructural systems that might otherwise be considered imperceptible. By paying attention to the arrangements of non-human actors of an app, its menus, its icons, its swipes and taps, they argue that it is possible to identify ‘master narratives’ which declare particular understandings about the world. Simple examples include the implicit hierarchical arrangement of ‘male’ and ‘female’ in a drop-down menu, which is clearly not abiding by any alphabetical logic, and which also reinforces gender binaries.

To give some concrete examples of this, let me describe a few features from the Grab app, a Singaporean competitor to Gojek. For its operations in Indonesia, Grab collaborates with the OVO wallet to provide an integrated digital payment mechanism for drivers and customers. After engaging with a Grab driver, the app asks you to rate your experience by awarding the driver up to 5 stars. Beneath the stars are additional clickable icons, providing subtle illustrations of what the designers of the app consider to be a ‘cool vehicle’, or indicating that a ‘helpful driver’ is one that carries your luggage. Positioned there beneath the stars, the implication is that these are criteria by which you might make your star-based rating. Furthermore, the distance between 1 and 5 stars is just a thumb swipe, but for the driver, the difference can be between preferential algorithmic treatment and automatic suspension. Drivers expressed how customers would rate them poorly for not appeasing their requests, even if these fell outside of the expected terms set up by the app, such as going a different route, or making a stop at the ATM or grocery store on the way, without offering additional payment. “Pity the driver who got one star”, as one driver explained, because it means the loss of access to the platform and thus their livelihood. In some cases, drivers described the companies even withholding their digital balance while the account was suspended, which they likened to theft.

The private sequestration of money becomes even more clear when examining the infrastructural design of these digital wallets. I initially assumed that drivers, like other users, had one digital wallet – after all, I was paying with my Go-Pay wallet to what I assumed was their Go-Pay wallet. Drivers are provided with three wallets in their version of the app; a ‘cash’ wallet used to store their digital earnings, and a ‘credit’ wallet, from which the company extracts their 20 per cent cut of the earnings from trips, and finally a direct link to the commercial wallet: Go-Pay for Gojek drivers, and OVO for Grab drivers. Earnings from the ‘cash’ wallet can be withdrawn as rupiah at an ATM, but it is also used to maintain a balance on the credit wallet, without which drivers are blocked from receiving new customer orders. The commercial wallet, a stand-alone wallet app in the case of OVO, allows them to exchange earnings directly into digital credit to be spent as regular consumers. One driver described how he always earmarked all the income he earned by driving part-time as ‘luxury money’, depositing it directly in his OVO wallet rather than withdrawing it as cash. By using his earnings as OVO credit, he gained access to heavily discounted cinema tickets or food and shopping at the mall. Meanwhile, the company behind OVO generated both a cut of each transaction and valuable transactional metadata (O’Dwyer, 2018). Arguably this is why much of the design of these apps orients users towards cashless transactions. Conveniently for the app companies, they have an extensive network of agents ready to facilitate customers wanting to exchange cash for digital credit. Through the app, drivers can transfer the contents of their ‘cash wallet’, thus ‘topping up’ the digital wallet of a customer, and receiving the equivalent cash value in return.

Digital payment proponents often argue that digital money is somehow safer than cash; in the sense that cash can be stolen, but digital money is tied to an account, and can thus be downloaded onto a new device if stolen. However, as my fieldwork continued in 2019, drivers who worked for the Grab app, and thus relied on the OVO digital wallet infrastructure, started expressing fears of what they called ‘OVO theft’; customers stealing the balance of a drivers digital wallet. Based on my experience of the affordances and limitations of the apps design, I could not imagine how customers could access the drivers’ wallet in such a way. When asked to explain further, one driver vaguely suggested that it was due to ‘hypnosis’.

Companies such as Gojek or OVO are often referred to as providing peer-to-peer payments, and generally, they present themselves as neutral intermediaries who simply provide a platform for exchange between users. In practice, these users can be divided into service provider and service customer, which already represents a hierarchical relationship rather than the equality we associate with being peers. Through my recording of screenshots, I had become aware of ways in which the apps nudged me to increase my digital transactions, and I was becoming increasingly aware of ways in which they were also imposing specific dynamics between myself and the drivers. As the intermediaries of that exchange relationship, they exert a great deal of influence over the terms of the exchange. One of the ways this is made tangible, is through the design of the app interfaces.

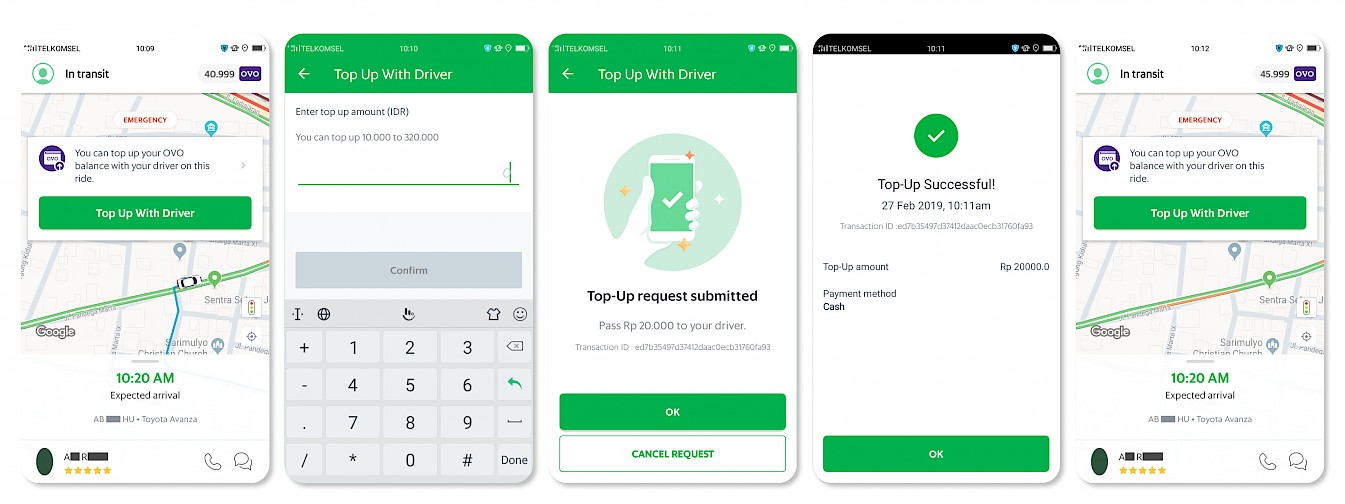

The screenshots below are from an interaction that I had with a Grab driver. They illustrate, from the customers perspective, the process of requesting and receiving a digital ‘top up’ of an OVO digital wallet. Once I enter the vehicle, the app covers most of the map with an uncloseable splash screen with a dominating green button, encouraging me to top up my balance with the driver. After clicking the button, the next screen informs me that I can request between 10.000 to 320.000 rupiah from the driver and gives me the option to enter a figure. In-person, I negotiate briefly with the driver, and we agree on 20.000, which is about the same as what I just paid him for the trip. Uang memutar he laughs, money goes around. The app now shows me a comforting image, with a sparkling green checkmark; my request has been successfully submitted! The driver reaches for his phone, makes some rapid taps, and almost instantly a new splash screen appears, telling me that the top up has been successful. As I hand 20.000 in cash to the driver, he asks me to confirm that the transaction went through. The screen returns to the map, and irritatingly, the uncloseable green button is still there.

Screenshots of a transaction made from the Grab app on 11th of April 2019. Recorded by author.

Screenshots of a transaction made from the Grab app on 11th of April 2019. Recorded by author.

There are a few things that the customer does not see in this interaction. Firstly, when the app tells me how much money I can request, it is actually showing me the entire contents of the driver's own account: his ‘cash’ wallet. Secondly, when I make the request, the driver receives a notification that the customer has requested a top up. Upon clicking the notification, a splash screen appears, detailing the amount requested. There is a graphic showing cash money moving in one direction, and digital money moving in another. The text reads: “Get money from the passenger to make a top up. The amount will be taken from your Cash Wallet.” There is another dominating green button, but this one reads “Collect money”. Once the driver clicks the button, the digital transaction takes place, and the driver is supposed to collect the equivalent amount of cash from the customer. It is notable, that there is no button to decline the transaction. The button does not even say “Confirm transaction”: the transaction is inevitable and done at the behest of the customer. There is no real agency here. As digital money agents, the drivers and their entire digital balances are simply made available to the customer. And this is the moment of ‘hypnosis’, in which a passenger manages to leave this transaction without the driver receiving the cash compensation. Perhaps the driver was hypnotized. Perhaps conned, perhaps outright robbed, perhaps the passenger simply forgets to hand over the cash before leaving the vehicle. Either way, the design of the app clearly both exposes and disadvantages the driver. It is important to keep in mind that the threat of suspension keeps drivers hostage to both customers and company, meaning that even if they have the option to cancel a transaction, they might still feel obliged to go through with it, to appease the passenger.

The apps position the drivers in such a way that they incentivise and facilitate the increasing access to and use of digital payments by the general population. These built-in mechanisms are those by which the company earns its money. Meanwhile, the risk involved is loaded onto the drivers themselves under the guise of peer-to-peer transactions and neutral platforms, camouflaged through attractive icons and the feeling of a seamless exchange experience for customers. While Grab has since changed some elements of the exchange, such as the ability of customers to see the driver’s balance, it is nevertheless a revealing moment as to how these allegedly neutral apps impose specific conditions upon their users, configuring their relationship to one of unequal power in the so-called P2P exchange. The not yet of the barista is an important reminder that these technologies and interfaces are in continuing development, and their increasing uptake requires careful examination of how they implement specific norms or measures that discourage or encourage behaviours in accordance with their own economic interests. It also draws attention to the importance of considering how our designs themselves could align with and support more equal exchange relationships.

Dieter, M., Gerlitz, C., Helmond, A., Tkacz, N., van der Vlist, F., Weltevrede, E., 2018. Store, interface, package, connection: Methods and propositions for multi-situated app studies (Working Paper No. 4). Collaborative Research Center 1187 Media of Cooperation, Universität Siegen.

Light, B., Burgess, J., Duguay, S., 2018. The walkthrough method: An approach to the study of apps. New Media & Society 20, 881–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816675438

O’Dwyer, R., 2018. Cache society: transactional records, electronic money, and cultural resistance. Journal of Cultural Economy 12, 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2018.1545243

Pfaffenberger, B., 1992. Technological Dramas. Science, Technology, & Human Values 17, 282–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/016224399201700302

Star, S.L., 1999. The Ethnography of Infrastructure. American Behavioural Scientist 43, 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326

Zelizer, V.A., 1996. Payments and Social Ties. Sociological Forum 11, 481–495.