One of the two steel boxes with equipment for emergency money. Photo: John Lee, 2011.

One of the two steel boxes with equipment for emergency money. Photo: John Lee, 2011.

Compression tests, photographic negatives for the production of printing plates, scale printing, and numbering machines (small machines for banknote numbering). Photo: John Lee, 2011.

Compression tests, photographic negatives for the production of printing plates, scale printing, and numbering machines (small machines for banknote numbering). Photo: John Lee, 2011.

A contemporary 50 kroner note from the 2009-11 series with a bridge motif.

A contemporary 50 kroner note from the 2009-11 series with a bridge motif.

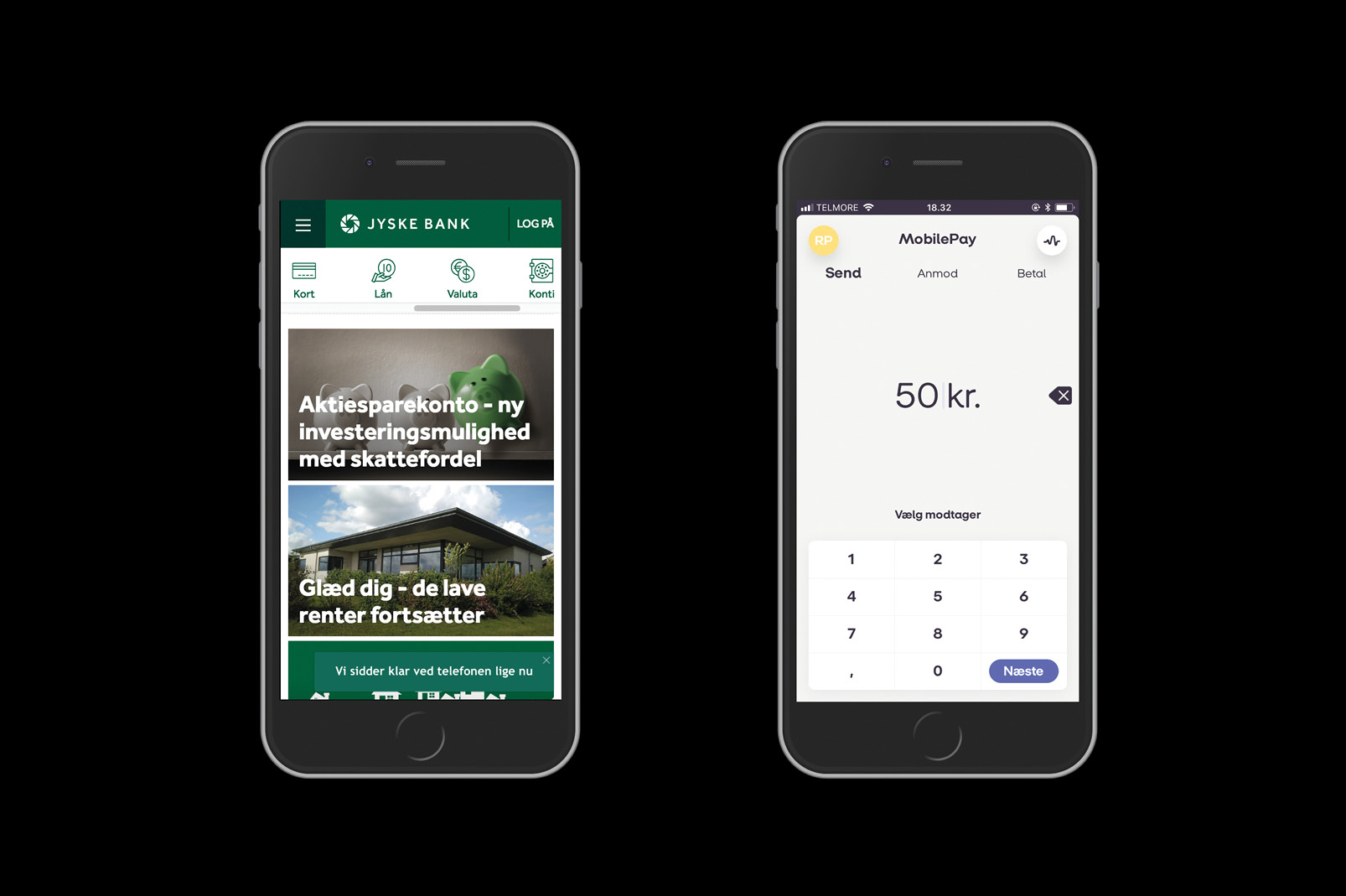

To the left: Example of digital money of account being iconized as cash. Example of digital money of account being iconized as cash. Pictograms at the top of Jyske Bank's website. To the right: On MobilePay's interface, the money appears as numbers on a screen.

To the left: Example of digital money of account being iconized as cash. Example of digital money of account being iconized as cash. Pictograms at the top of Jyske Bank's website. To the right: On MobilePay's interface, the money appears as numbers on a screen.

The foyer in the National Bank of Denmark furnished with Swan chairs. Photo: The National Bank of Denmark.

The foyer in the National Bank of Denmark furnished with Swan chairs. Photo: The National Bank of Denmark.

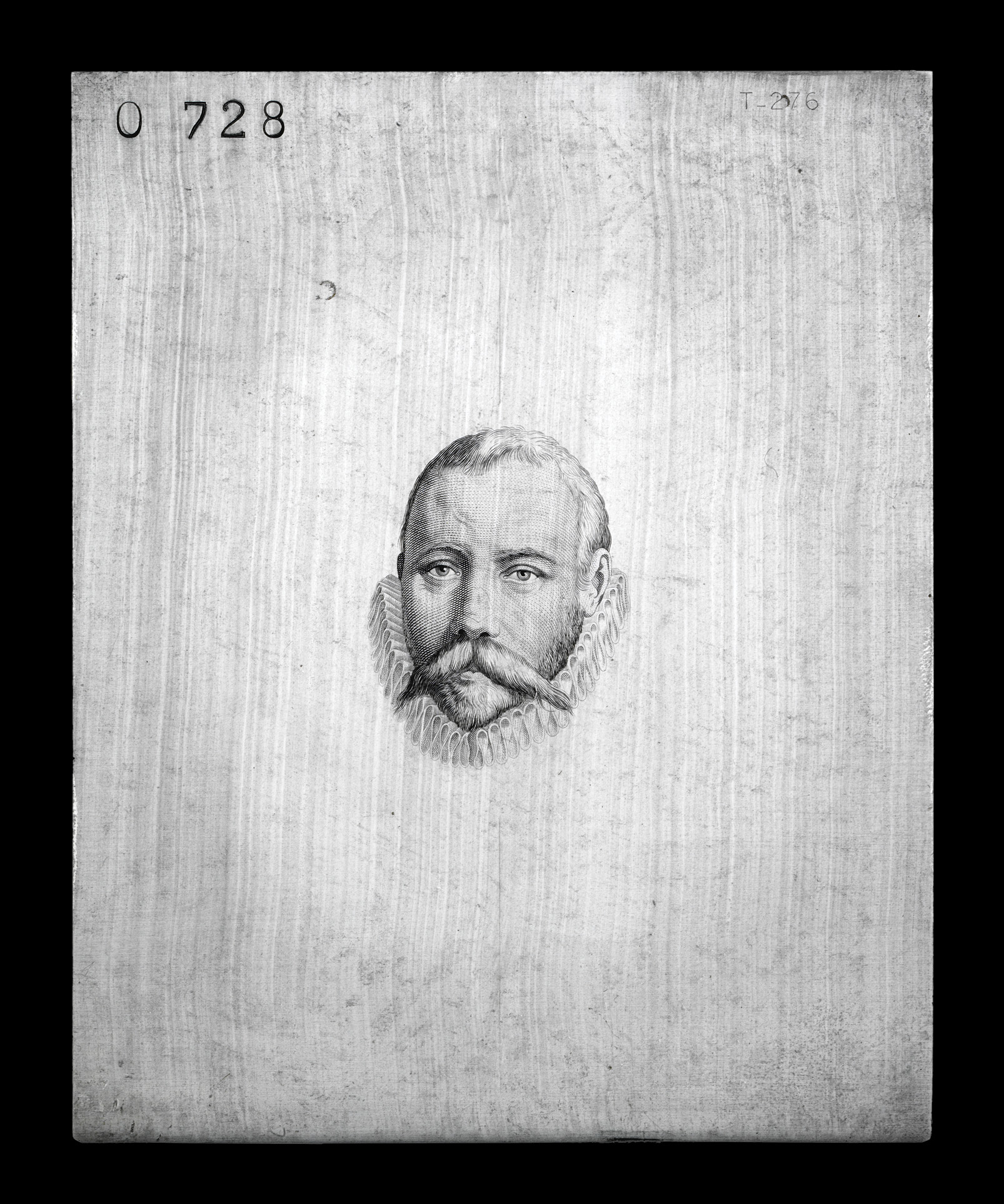

Steel printing plate with a portrait of the astronomer Tycho Brahe for the production of emergency banknotes. Photo: John Lee, 2011.

Steel printing plate with a portrait of the astronomer Tycho Brahe for the production of emergency banknotes. Photo: John Lee, 2011.

In 2008, somewhere in the National Bank of Denmark in Copenhagen, the seal on two steel boxes was broken. The contents made up an antiquated crisis package from the Cold War contingency plan, including all the necessary equipment for the production of special emergency money. In case of an atomic annihilation or an invasion of Zealand and Copenhagen, these small toolkits could form the basis for a new production and a redesign of banknotes on Funen and in Jutland. The Cold War contingency plan for the monetary system probably began in the beginning of the 1950s, and from 1965-72 the emergency money and the contents of the two steel boxes were designed and developed. The intention was to enable the continuation of the Danish krone as a state value guarantee, and therefore the emergency money should be at the same time recognizable and different from the banknotes of the time. To solve this task, portraits of famous Danes from the previous banknote series of 1952 were used in the visual identity of the emergency money. These portraits both had a security graphic quality and a level of detail that was difficult to falsify and at the same time easy to associate with money, because of the style motifs from the previous banknotes. The emergency money was meant to function in a transitional period, while the more cumbersome copper print production of the ordinary banknotes was established.

Like two black boxes from a catastrophe that never occurred, the anonymous steel boxes bear witness to the importance of money for the maintenance of society and the nation state. At the same time, they show that the monetary system and the institutions that maintain it have changed. In relation to the time of the discovery of the steel boxes, in the year of the financial crisis of 2008, the contents and the design of the emergency money appear as a relic of the past. There is no similar example concerning the financial crisis, where the emergency measures were Bank Package 1 and 2, which primarily secured the liquidity of the banks. Today, money has changed form and design from cash to digital money, not by a sudden catastrophe, government intervention, or democratic decision, but as a result of a gradual technological and political development.

Today, around five percent of the total Danish money supply consists of cash and is produced on the initiative of the National Bank of Denmark, even though the production has moved abroad. The remaining 95 percent of the Danish money supply is still produced in Denmark. It is digital money deposited in our bank accounts, and this money has a design completely different from cash. The digital money appears to the user as numbers in a spreadsheet on a screen. It is created by the private banks when they provide loans to their customers, as the customers' accounts are revalued with the borrowed amount.

The Danish krone is a living example of the ambiguous nature of the money phenomenon, as cash and digital money are still perceived as the same thing and continue to be exchanged as the same unit of value. From a design perspective, however, they do not have much in common. In this article, we examine this ambiguous phenomenon by examining the Danish krone both as physical objects and digital money of account. By viewing money as a design, the forms, relations, systems, and fictions that different forms of money consist of and are part of, is made clear. This approach highlights the different operational and systemic nuances of money.

Cash are physical coins and banknotes. Today, the Danish krone coins consist of 50 ører, 1 kroner, 2 kroner, 5 kroner, 10 kroner and 20 kroner. The series of coins contains different metal alloys and has different weights and sizes. They are decorated and embossed with national and royal symbols. The banknotes consist of five units of measurement ranging from a note of 50 kroner to a note of 1000 kroner. Like the coins, the banknotes are also differentiated from each other in size, having the length increased by one centimeter every time the amount of the note goes up. For example, the 1000 kroner note is four centimeters longer than the 50 kroner note. The material, dirt-repelling cotton paper, is the same, but each note has its own motif and color. The motif series was created on the basis of a working group with eight different artists, who were subsequently selected for a competition. Karin Birgitte Lund's proposal was selected as the basis for the visual expression of the banknotes and has motifs of Danish bridges and ancient finds. The banknote series came into circulation in 2009-11(1). In addition to the aesthetic expression of the banknotes, they also consist of a number of designed security measures. Several newer security elements are used, e.g. a window thread with a moving wave pattern, a hologram that reflects light in different colors, as well as a watermark and a hidden safety thread. Of older designed security elements are used effects such as copper print, numbering and signatures of the directors and the chief treasurer of the National Bank.

Considered a practical everyday design, the Danish cash consist of various units of measurement, each of which has their own value or representation of value inscribed in the number of kroner. Cash has tactile and physical qualities – you can touch them, weigh them in your hand, put them in your mouth and eat them, burn them or sense their physical, visual appearance and expression in many other ways. This allows them to be counted, differentiated from one another and used for calculations.

In a study from the early 1990s, sociologist Viviana Zelizer describes how suburban American housewives make their own cash savings systems by distributing the coins and notes in respective envelopes and store them in metal cans in order to meet different purposes. The example shows that cash are autonomous items that allow users to utilize and manage them in different ways. Their physical condition ensures a high degree of anonymity, as one can buy goods without the money being registered and tracked, without knowing where the money came from, or how much money has been spent in the transaction in question. In this way, in principle, you can do with cash whatever you want. It can be stored away in small metal cans, used as payment, drawn on, or burned.

The cash is a piece of operational design that has a practical purpose in making possible transactions between actors of society through a physical transfer. Since it is created by a state actor, the National Bank of Denmark, it is basically made available for society free of charge. This system makes the cash applicable for all citizens who are in possession of it.

Today, the physical cash can be described as design treasures that are entirely or at least partly disappearing from society. Their function is no longer a fundamental precondition for the Danish monetary system, as was the case during the Cold War. Like Danish design classics such as the Swan and the Oxford chair, which represent the idea of the functional, honest, and democratic chair (and is part of the interior of the National Bank of Denmark), cash appear as icons of our idea of money. When the National Bank of Denmark arranges design competitions in which they invite architects, designers, and artists to decorate and design the banknotes, then the banknotes are further inscribed in a tradition of Danish design and handicrafts. Hence, there is a dual use of design in relation to contemporary cash. As design objects, cash has an internal logic where design is part of the aesthetic process of the visual and physical expressions of cash. And at the same time, cash can be seen as a systemic design, where the single monetary objects have an external function in relation to the overall monetary system, and where they are historically rooted in an operational system used to control for example inflation and money supply. The external function of cash today is also embedded in the creation of images and signs around money and finance, which help the user to understand transaction rituals and relationships.

Cash is now over-represented as icons, while their system and use have been reduced. The digitization of money creates a gap between what is perceived as money – the cash – and what most money is – digital money of account. Banknotes and coins are reduced to pictograms and signs that help us understand transaction rituals and forms of payment, just like the icons from the graphic user interfaces of the mid-1980s home computers. Today, these signs help the user to understand the interfaces of the banks and the different means of payment. This is seen in everything from signposting on ATM’s to logos like MobilePay (2) or the websites of banks. The cash is user interfaces that have been deprived of their operating system because of the digitization of money. The function of today’s cash is reduced to visual associations.

From a design perspective, it is a pivotal point that the user of digital money cannot perceive or interact with it without design. The design visualizes and organizes the user interfaces that make the numbers, the bookkeeping, and the bank account visible. Money is embedded in the technology in which it is represented, and in the systems that maintain and register its circulation. Digital money can only be accessed and handled as part of a larger system of electronic and digital waves, wires, circuits, screens, digital accounting systems, payment cards, payment machines and terminals, masts, mobile payment applications, NemID (3) and more. Design plays a role in shaping all these elements, but the system in which the elements are embedded can also be seen as a systemic design. The user can sense and see the physical sub-elements of the monetary system, while the systemic design remains intangible and difficult to understand.

In his book The Stack, On Software and Sovereignty (2016), sociologist and design theorist Benjamin Bratton presents an architectural model he calls “the stack”. With this idea of the stack, he presents a model for how to map the complex globalized and digitized world. The model consists of 6 layers: Earth, Cloud, City, Address, Interface, and User. Each layer has its own social, political, and material conditions. An important point in mapping the stack is to create an overview of our complex digital world, but also to map and discuss sovereignty over the Internet as a geopolitical territory. The Danish digital money system and the digital money of account are part of this global and digitized stack.

In his talk at the exhibition Money Manual (4), anthropologist and author Brett Scott presented an onion-shaped model, where the digital money of account is the starting point at the center. As a layer around this center lie the data centers and user interfaces of the banks, and then can be added subsequent layers of different technologies and actors that expand the digital money system. The more layers, the more interests and business models are involved in managing and regulating the system. In the following description of the Danish monetary system, we have been inspired by both of these models.

More specifically, digital money of account is electronic signals or data stored on physical servers. To the user, they appear as digits in a spreadsheet on a screen of a digital device. The user interfaces make the money sensible and manageable for the users, which are both customers in private banks, companies, public institutions, and the banks themselves.

In Denmark, the banks’ own data centers and software systems enables the customers’ online banking and mobile banking interfaces, and there are five data centers run by the banks. The two major banks, Danske Bank and Nordea, each have their own data center. Danske Bank has a data center in Ejby, but does not want to disclose where their money of account is stored. Likewise, Nordea fail to disclose where their data is stored. In addition, three consolidations of several large and small banks have joined forces to develop digital systems. These are BEC, formerly Bankernes EDB Central, which is headquartered in Roskilde and hosts Nykredit and Spar Nord, as well as a number of foreign banks. BEC also has the National Bank of Denmark as a customer. Then there is Bankdata, which is headquartered in Fredericia and hosts, among others, Jyske Bank's and Skjern Bank's digital data. Finally, there is Sparekassernes Datacentral (SDC) with head office in Ballerup. Originally SDC was only for savings banks, but today it also has banking companies and other Nordic banks as customers. The above-mentioned data centers are responsible for designing, maintaining and securing the digital data, software systems, and interfaces through which both the employees of the banks, corporate customers, public institutions, and private customers can interact with the digital money of account.

The Dankort was introduced on the Danish market in 1984 and has played a major role in the spread of digital money of account. The payment card had a slow start-up, but consumers gradually adopted it, and today the payment card is the predominant means of payment in Denmark. In 2017, Danes completed almost 1.4 billion Dankort transactions with a total value of more than 400 billion kroner. The Dankort was developed by Pengeinstitutternes Købe- og Kreditkortaktieselskab (PKK), which was established in 1979 by the Danish banks to develop an efficient electronic payment system for the Danish market. Today, most payment cards in Denmark are a combination of VisaDankort. Visa is a joint-stock company whose products in Denmark are administered by Nets. When the payment card is used abroad, the Visa component is automatically used, while the Dankort component is automatically used for transactions in Denmark. Nets has a history dating back to the 1960s, when Danish financial institutions joined forces to develop and invest in different electronic payment systems, the Dankort included. Today, Nets is owned by three American private equity funds.

As a design system, the VisaDankort is a debit card and not a credit card, with which it is often confused. The difference is that you can get credit from your bank on a credit card and then pay it back later. On a debit card, you must have money on the card in order to use it, although today it is also possible to overdraw most debit cards using an overdraft. From a design perspective, the payment card is a mediator for the digital money of account, as there is no actual physical contact with the money. From a household economic perspective, the payment card is not very user-friendly, because you are never in contact with your cash supply in your bank account. The number accessed through the payment card is the price of the purchase, that is, the amount of money that has to be deducted from the user's bank account. As a payment system, the payment card is efficient because it makes the payment session uncomplicated and seamless.

MobilePay was developed by Danske Bank in collaboration with the design company Designit and was launched on the Danish market in May 2013. Due to a better user experience, presumably, MobilePay quickly outperformed the competing mobile payment application Swipp, which was developed by an association of several private banks. In 2017, most Danish financial institutions joined MobilePay, and the company is now independent and operates as such, though it is still owned by Danske Bank.

As a system, MobilePay is developed as a layer on top of Nets' payment system, where the user registers his or her payment card in the application and then makes mobile money transactions. The big question is how long MobilePay will keep Nets as an intermediary in the payment transaction before switching to a direct money transaction between the banks.

Today, other companies also offer solutions in the realm of payment, for example the so-called fin-tech companies – financial technology companies. In Denmark, companies such as Lunar Way offer a mobile application for transactions and savings, while Spiir and YNAB offer a mobile-based accounting and budgeting application. Silicon Valley-based companies like Apple Pay and Facebook are also involved in this field. From a design perspective, the new companies contribute with innovative solutions in the administration and management of the digital money of account, because they allow consumers to improve the use and management of the money. But it is also yet another layer of actors and business models that must profit from the money spending.

As a man-made and designed phenomenon, money is one of the most tangible and yet maybe the most abstract everyday phenomena that man uses. In the historical example of emergency money, the monetary system appears as a delimited and manageable microcosm. The contents of the steel boxes have human proportions and can be seen as a closed sphere, in which sub-elements can both stand out independently and be put in relation to each other and to society. The two 'toolkits' testify to a societal desire and ability to control and regulate the monetary system as a vital part of society. Today, cash is lacking an operational function in the monetary system, as they primarily appear as symbolic representations of digital money of account.

In a complex digitized age, the user's attention to everyday technology is dissolved and distorted. By mapping and looking at the embedment of digital money in the digital technology, the abstract can be made tangible and visible. In this way, the distinctions between the different monetary systems are highlighted, which makes it possible to see the qualities and challenges of each of them. At the same time, by making this overview, there is a potential for a nuanced discussion about the sovereignty over money. Who should create them? What needs do they have to meet and for whom? And with it, how the monetary system should be designed operationally and systemically.

(1) In November 2020 The National bank of Denmark issued new 500 kroner banknotes very similar to the existing ones, but with enhanced security measures. The new 500 kroner notes will soon be followed by new versions of the other banknotes

(2) MobilePay is a mobile payment application developed by Danske Bank.

(3) NemID is a common log-in for public and private self-service solutions and for online banking.

(4) Exhibition in Blaa Galleri on Nørrebro, Copenhagen in October 2017 about the creation and design of money

I 2008 et sted i Danmarks Nationalbank i København blev forseglingen på to stålkasser brudt. Indholdet udgjorde en hengemt krisepakke fra den kolde krigs katastrofeberedskab, alt det fornødne udstyr til fremstillingen af særlige nødpenge. I tilfælde af den atomare udslettelse eller invasionen af Sjælland og København kunne disse små værktøjskasser udgøre grundlaget for en nyproduktion og et re-design af pengesedler på Fyn og i Jylland.

Den kolde krigs beredskabsplan for pengesystemet begyndte formentlig i begyndelsen

af 1950erne, og fra 1965-72 blev nødpengene og indholdet til de to stålkasser designet og udviklet. Intentionen med de to kasser var at muliggøre en videreførelse af kronen som en statslig værdigaranti, og de særlige nødpenge skulle derfor både være genkendelige og skille sig ud fra datidens pengesedler. For at løse denne opgave blev der i nødpengenes visuelle identitet anvendt portrætter af kendte danskere fra den tidligere pengeseddelsserie fra 1952. Disse portrætter havde både en sikkerhedsgrafisk kvalitet og detaljegrad, der var svær at forfalske, og var samtidig nemme at associere med penge grundet deres motivstil fra de tidligere pengesedler. Nødpengene skulle fungere i en overgangsperiode, mens man fik etableret den mere besværlige kobbertryksproduktion af de almindelige pengesedler.

Som to sorte bokse fra en katastrofe der aldrig indtraf, vidner de anonyme stålkasser i dag om pengenes betydning for opretholdelsen af samfundet og nationalstaten. Samtidig vidner de om, at pengesystemet og de institutioner som opretholder det har ændret sig. I relation til tidspunktet for opdagelsen af stålkasserne, i det finanskriseramte 2008, fremstår indholdet og nødpengenes design som et levn fra fortiden. Der er ikke noget tilsvarende eksempel i forhold til finanskrisen, hvor nødforanstaltningerne var Bankpakke 1 og 2, som primært sikrede bankernes likviditet.

Pengene har i dag skiftet form og design fra kontanter til digitale penge, ikke i kraft af en pludselig katastrofe, statslig intervention eller demokratisk beslutning, men som et resultat af en glidende teknologisk og politisk udvikling. I dag består cirka fem procent af den samlede danske pengemængde stadig af kontanter og bliver produceret på initiativ af Danmarks Nationalbank. Produktionen er dog flyttet til udlandet. De resterende 95 procent af den danske pengemængde produceres stadig i Danmark. De er digitale penge, som er indeståender på vores bankkonti, og disse penge har et helt andet design end kontanterne. De digitale penge fremstår for brugeren som tal i et regneark på en skærm. De skabes af de private banker, når de yder lån til deres kunder, ved at kundernes konti bliver opskrevet med det lånte beløb.

Den danske krone er i dag et levende eksempel på pengefænomenets flertydige væsen, hvor kontanter og digitale penge stadig opfattes som det samme og fortsat udveksles som samme værdienhed. Fra et designperspektiv har de ikke meget tilfælles. I denne tekst undersøger vi dette flertydige væsen med udgangspunkt i en beskrivelse af de danske kroner som både fysiske objekter og digitale kontopenge. Ved at anskue penge som design, tydeliggøres de former, relationer, systemer og fiktioner som forskellige pengeformer består af og indgår i. Denne tilgang fremhæver pengenes forskellige operationelle og systemiske nuancer.

Kontanter er fysiske mønter og pengesedler. I dag består de danske kronemønter af 50-ører, 1-kroner, 2-kroner, 5-kroner, 10-kroner og 20-kroner. Serien af mønter indeholder forskellige metallegeringer og har forskellig vægt og varierende størrelser. De er udsmykket og præget med nationale og royale symboler. Pengesedlerne består af fem måleenheder fra en 50-kroneseddel op til en 1000-kroneseddel. Pengesedlerne differentieres også fra hinanden i størrelse, hvor længden forøges med en centimeter hver gang sedlens beløb stiger. Eksempelvis er 1000-kronesedelen fire centimeter længere end 50eren. Materialet, smudsafvisende bomuldspapir, er det samme, men hver seddel har hver sit motiv og farve. Motivserien blev til på baggrund af en arbejdsgruppe med otte forskellige kunstnere, som efterfølgende blev udvalgt til en konkurrence. Karin Birgitte Lunds forslag blev udvalgt som udgangspunkt for sedlernes visuelle udtryk og har motiver af danske broer og oldtidsfund. Seddelserien kom i cirkulation 2009-11.

Udover pengesedlernes æstetiske udtryk består de også af en række designede sikkerhedsforanstaltninger. Af nyere sikkerhedselementer anvendes bl.a. vinduestråd med bevægeligt bølgemotiv, hologram, der reflekterer lyset i forskellige farver, samt vandmærke og skjult sikkerhedstråd. Af ældre sikkerhedselementer anvendes sikkerhedsgrafiske virkemidler som eksempelvis kobbertryk, nummerering og underskrifter af nationalbankens direktører og hovedkasserer.

Betragtet som et praktisk anvendt hverdagsdesign består de danske kontanter af forskellige måleenheder, som har hver deres værdi eller repræsentation af værdi påskrevet i antal kroner. Kontanter har taktile og fysiske egenskaber – man kan røre ved dem, veje dem i hånden, putte dem i munden og spise dem, brænde dem eller på anden måde sanse deres fysiske visuelle fremtoning og udtryk. Dette gør, at de kan tælles, differentieres fra hinanden og bruges

til regnestykker. I et studie fra begyndelsen af 1990erne beskriver sociologen Viviana Zelizer, hvordan amerikanske husmødre i forstæderne laver deres egne opsparingssystemer med kontanter ved at fordele dem i forhold til forskellige formål i hver deres konvolut for at gemme dem væk i metaldåser. Eksemplet viser, at kontanterne er autonome genstande, som tillader brugerne at anvende og håndtere dem på forskellige måder. Deres fysiske tilstand

sikrer en høj grad af anonymitet ved, at man kan købe varer uden, at det bliver registret og sporet, hvor pengene kommer fra eller hvor mange penge, der er anvendt i den pågældende transaktion. Det vil sige, at man i princippet kan gøre med dem, hvad man vil. De kan gemmes væk i små kagedåser, bruges som betaling, tegnes på eller brændes.

Kontanterne er et stykke operationelt design, der har et praktisk formål i at gøre transaktioner mulige mellem samfundets aktører ved en fysisk overdragelse. Da de er skabt af en statslig aktør, Nationalbanken, er de i udgangspunktet noget, der stilles gratis til rådighed for samfundet. Dette system gør dem anvendelige for alle borgere, der er i besiddelse af dem.

Fra et designperspektiv er det en central pointe, at brugeren af digitale penge ikke kan percipere eller interagere med pengene uden design. Det er design, som visualiserer og organiserer de brugerflader, som gør tallene, bogholderiet og bankkontoen synlig. Pengene er indlejret i den teknologi, som de er repræsenteret i og i de systemer, som opretholder og registrerer deres cirkulation. Digitale penge kan kun tilgås og håndteres som en del af et større system af elektroniske og digitale bølger, ledninger, kredsløb, skærme, digitale bogføringssystemer, betalingskort, betalingsautomater, betalingsterminaler, mobilmaster, mobile betalingsapplikationer, nemID med mere. Design spiller en rolle i forhold til udformningen af alle disse elementer, men det system, som elementerne er indlejret i, kan også anskues som et systemisk design. Brugeren kan sanse og se de fysiske delelementer af pengesystemet, mens det umiddelbart er uhåndgribeligt at forstå og overskue det systemiske design.

I bogen The Stack, On Software and Sovereignty (2016) præsenterer sociologen og designteoretikeren Benjamin Bratton en arkitektonisk model, han kalder The Stack eller ’stakken’. Med denne ide om stakken præsenterer han en model for, hvordan man kan kortlægge den komplekse globale og digitaliserede verden. Modellen består af 6 lag: jorden, skyen, byer, adresser, brugerflader og brugere. Hvert lag har deres sociale, politiske og materielle betingelser. En vigtig pointe med at kortlægge stakken er at skabe et overblik over vores komplekse digitale verden, men også at kortlægge og diskutere suverænitet over internettet som geopolitisk territorium. Det danske digitale pengesystem og de digitale kontopenge er en del af denne globale og digitaliserede stak. Antropolog og forfatter Brett Scott præsenterede i sit foredrag under udstillingen Pengemanual en løgformet model, hvor de digitale kontopenge er udgangspunkt og i centrum. Herefter lægger først bankernes datacentre og brugerflader sig som et lag udenpå og derefter kan andre lag af forskellige teknologier og aktører, som udvider det digitale pengesystem, tilføjes. Jo flere lag, jo flere interesser og forretningsmodeller er med til at forvalte og regulere systemet. I følgende beskrivelse af det danske pengesystem har vi ladet os inspirere af begge disse modeller.

1. lag

Elektroniske signaler: Brugerflader og brugerne

Konkret er digitale kontopenge elektroniske signaler eller data lagret på fysiske servere. For brugeren optræder de som cifre i et regneark

på en skærm i et digitalt apparat. Det er bruger-

flader, som gør pengene sanselige og håndterbare for brugerne, som er både private bankkunder, virksomheder, offentlige institutioner og bankerne selv.

2. lag

Den digitale geografi: Datacentralerne

I Danmark er det bankernes egne datacentraler og softwaresystemer, der gør brugernes netbank- og mobilbanksinterfaces mulige. Der er fem bankdrevne datacentraler. De to store banker, Danske Bank og Nordea, har hver sin datacentral. Danske Bank har et datacenter i Ejby, men ønsker ikke oplyse, hvor deres kontopenge er lagret. Nordea vil ligeledes ikke oplyse, hvor deres data opbevares. Derudover findes der tre andre sammenslutninger, hvor flere store og mindre banker er gået sammen om at udvikle digitale systemer. Det drejer sig om BEC, tidligere Bankernes EDB Central, som har hovedsæde i Roskilde og blandt andet hoster Nykredit og Spar Nord samt en række udenlandske banker. BEC har også Nationalbanken som kunde. Yderligere er der Bank-

data, som har hovedsæde i Fredericia og blandt andet hoster Jyske Banks og Skjern Banks digitale data. Til sidst er der SDC, Sparekassernes Datacentral, som har hovedsæde i Ballerup og oprindeligt kun var for sparekasser, men nu også har bankvirksomheder og andre nordiske pengeinstitutter som kunder. De ovennævnte datacentraler står for at designe, vedligeholde og sikre de digitale data, softwaresystemer og interfaces, hvorigennem både medarbejderne i bankerne, virksomhedskunder, offentlige institutioner og private kunder kan interagere med de digitale kontopenge

3. lag

Den digitale infrastruktur: Betalingskort og Nets

Dankortet blev introduceret på det danske marked i 1984 og har spillet en stor rolle for udbredelsen af de digitale kontopenge. Betalingskortet havde en spæd opstart, men løbende tog forbrugerne det til sig, og i dag er betalingskortet det altdominerende betalingsmiddel i Danmark. I 2017 gennemførte danskerne knap 1,4 milliarder dankorttransaktioner med en samlet værdi på over 400 milliarder kroner.

Dankortet blev udviklet af PKK, Pengeinstitutternes Købe- og Kreditkortaktieselskab, som blev etableret i 1979 af de danske pengeinstitutter for at udvikle et effektivt elektronisk betalingssystem til det danske marked. I dag er de fleste betalingskort i Danmark en kombination af Visa/Dankort. Visa er et aktieselskab, hvis produkter i Danmark administreres af Nets. Når kortet benyttes i udlandet anvendes automatisk visa-delen, mens dankort-delen automatisk anvendes ved transaktioner i Danmark. Nets har en historie, som går helt tilbage til 1960erne, hvor danske pengeinstitutter gik sammen om at udvikle og investere i elektroniske betalingssystemer, blandt andet Dankortet. I dag ejes Nets af tre amerikanske kapitalfonde.

Som designsystem er Visa/Dankortet et debetkort og ikke et kreditkort, som det ofte forveksles med. Forskellen er, at man på et kreditkort kan få kredit hos sin bank, som man så senere betaler tilbage. På et debetkort skal man i princippet have penge på kortet, selvom det i dag også er muligt at trække over på de fleste debetkort ved hjælp af eksempelvis en kassekredit. Fra et designperspektiv er betalingskortet en mediator for de digitale kontopenge, da der ikke er nogen egentlig fysisk kontakt med de digitale kontopenge. Fra et husholdningsøkonomisk perspektiv er betal- ingskortet ikke særlig brugervenligt, fordi man aldrig er i kontakt med sin pengebeholdning på sin bankkonto. Det tal, betalingskortet og de dertilhørende betalingsterminaler giver adgang til, er prisen for købet – den pengemængde, som skal trækkes fra brugerens bankkonto. Som betalingssystem er betalingskortet effektivt, fordi det gør betalingsseancen ukompliceret og friktionsløs.

4. lag

Digitale ’hverdagskontanter’: MobilePay

MobilePay er udviklet af Danske Bank i samarbejde med designfirmaet Designit og udkom på det danske marked i maj 2013. Hurtigt udkonkurrerede MobilePay den konkurrerende mobilbetalingsapplikation Swipp, som var udviklet af en sammenslutning af flere private banker. Dette skyldes sandsynligvis, at MobilePay tilbyder en bedre brugeroplevelse. I 2017 tilsluttede de fleste danske pengeinstitutter sig MobilePay, og virksomheden blev et selvstændigt selskab, der stadig ejes af Danske Bank og fungerer som en selvstændig virksomhed.

Som system er MobilePay udviklet som et lag oven på Nets’ betalingssystem, hvor brugeren registrerer sit betalingskort i applikationen og derefter foretager mobilepengetransaktioner. Det store spørgsmål er, hvor længe MobilePay beholder Nets som mellemled i betalingstransaktionen i stedet for at overgå til en direkte pengetransaktion mellem bankerne.

5. lag

De nye fin-tech produkter

I dag er der også andre virksomheder, som byder ind på betalingsområdet, eksempelvis fin-tech virksomheder – finans-teknologiske virksomheder. I Danmark er det virksomheder som Lunar Way med deres transaktions- og opsparings-mobilapplikation, og Spiir og YNAB, som er en mobilbaseret regnskabs- og budgetlægningsapplikation. Også amerikanske Silicon Valley-baserede virksomheder som Apple Pay og Facebook begynder at byde ind på dette område. Fra et designperspektiv bidrager de nye virksomheder med innovative løsninger på området for administration og håndtering af de digitale kontopenge, fordi de forbedrer forbrugernes mulighed for at anvende og administrere de digitale kontopenge, men det er også endnu et lag med aktører og forretningsmodeller, som skal tjene penge på pengeforbruget.

Opsummering, terminal

Penge er som menneskeskabt og designet fænomen noget af det mest konkrete og samtidig måske det mest abstrakte hverdagsfænomen, som mennesket benytter sig af.

I det historiske eksempel med nødpengene fremstår pengesystemet som et afgrænset og overskueligt mikrokosmos. Indholdet af stålkasserne har menneskelige proportioner og kan anskues som en lukket sfære, hvori delelementer både kan stå frem selvstændigt og sættes i relation til hinanden og samfundet. De to ’værktøjskasser’ vidner om et samfundsmæssigt ønske om og evne til at styre og regulere pengesystemet som en vital del af samfundet. I dag har kontanterne en manglende operationel funktion i forhold til pengesystemet, hvor de overvejene optræder som symbolske repræsentationer for digitale kontopenge.

I en kompleks digitaliseret samtid opløses og forvanskes brugerens opmærksomhed på hverdagens anvendte teknologi. Ved at kortlægge og anskue de digitale penges indlejring i den digitale teknologi kan det abstrakte gøres konkret og synligt. Derved står forskellene mellem de forskellige pengesystemer frem, hvilket gør det muligt at se kvaliteterne og udfordringerne ved dem hver især. Samtidig skaber overblikket et potentiale for en nuanceret diskussion om suveræniteten over pengene. Hvem skal skabe dem? Hvilke behov skal de opfylde og for hvem? Og dermed, hvordan pengesystemet operationelt og systemisk skal designes.