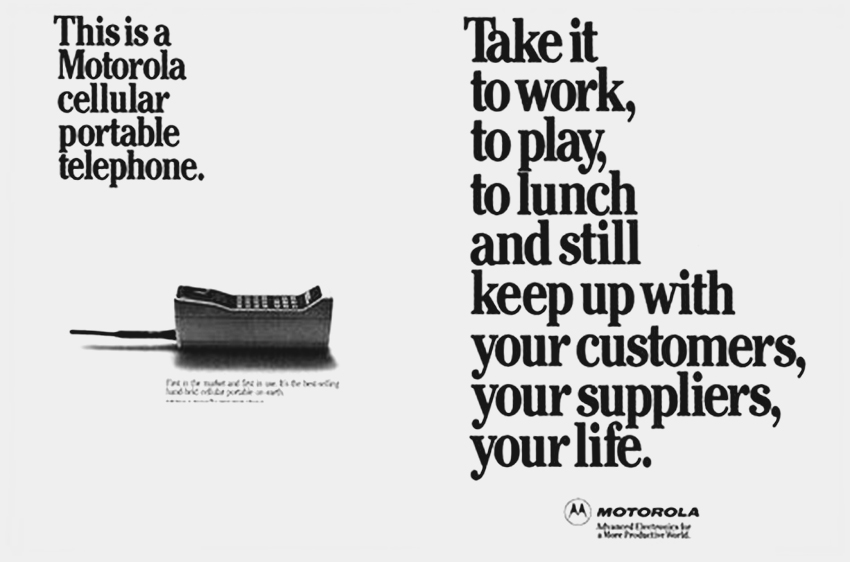

A Motorola advertisement for the DYNA T-A-C model (circa 1985).

A Motorola advertisement for the DYNA T-A-C model (circa 1985). A scene from the cartoon strip Dick Tracy.

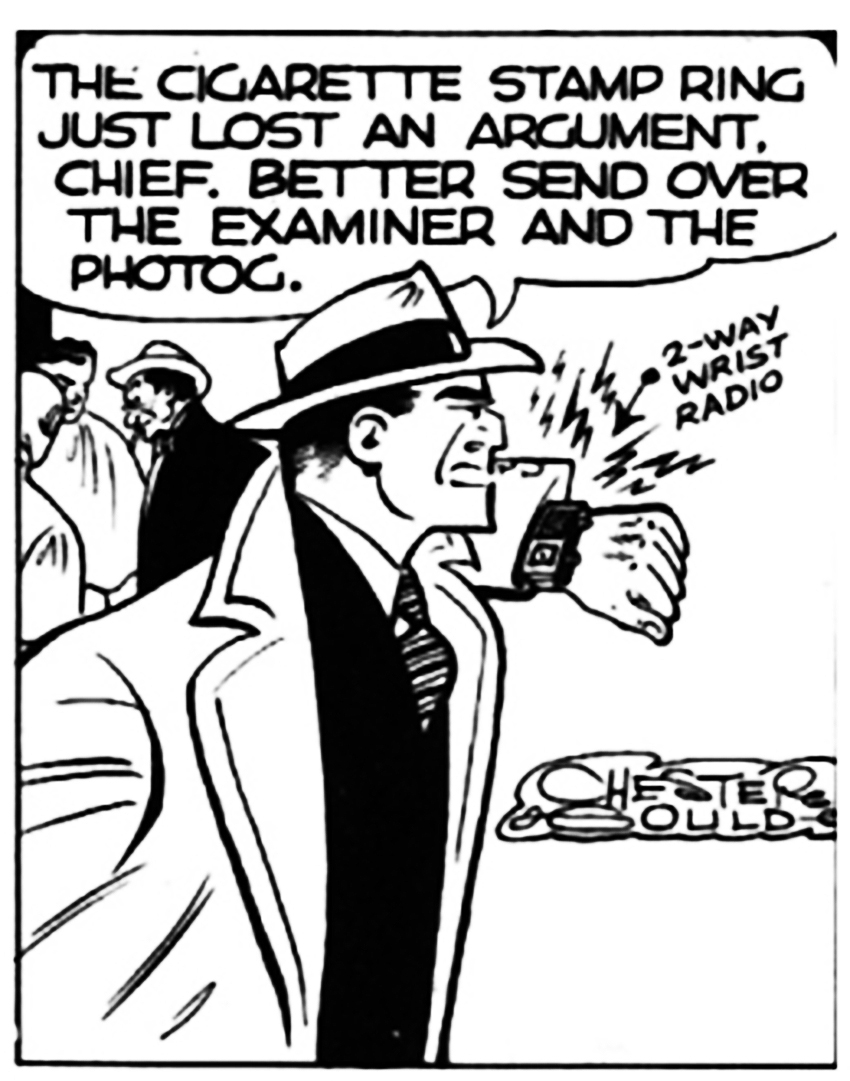

A scene from the cartoon strip Dick Tracy.

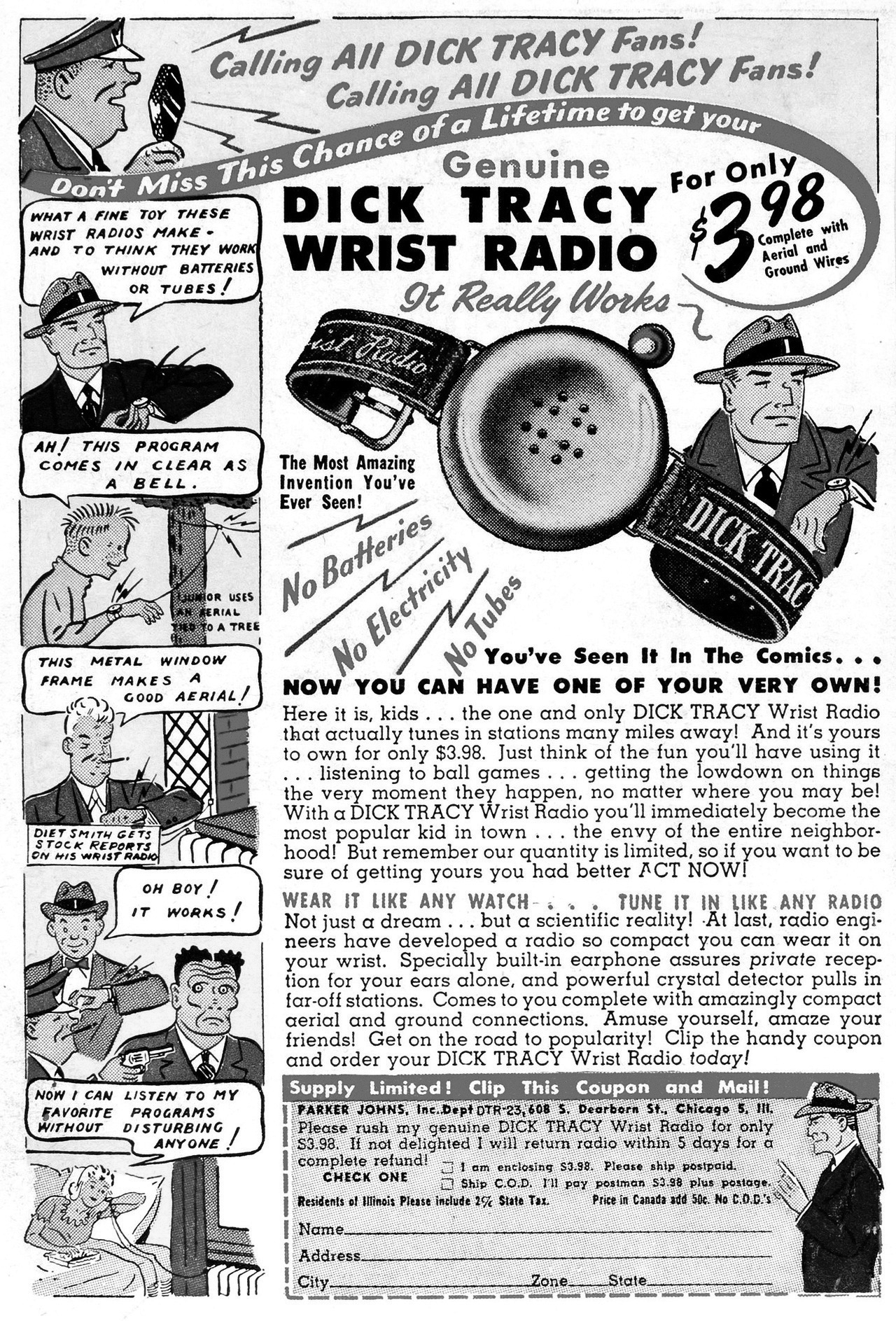

An advertisement for a Dick Tracy wrist radio.

An advertisement for a Dick Tracy wrist radio.

On the 3rd of April 1973 a group of nervous engineers and curious journalists gathered in the Hilton Hotel in New York City for a highly anticipated launch. At the centre of the attention was Marty Cooper, an affable Motorola engineer credited with the invention of the DYNA T-A-C 8000X, the world’s first hand-held mobile phone. Cooper had a lot riding on this launch, not least of all his ego. His enduring rivalry with Joel Engel, an engineer at Bell Labs, was well known. The Motorola team had been busy all morning, strategically positioning launch masts on nearby buildings in Manhattan, praying to the wireless gods that the first mobile call would go as planned. In front of onlookers, a journalist picked up the one-kilogram DYNA-TAC handset and dialled his wife at home. It worked. Although he would later write that she sounded a little “tinny”. Cooper, hyped from the success of the launch, dashed outside to a busy Manhattan sidewalk to make another call. Oblivious to the cars he almost stepped into oncoming traffic. He dialled Bell Labs to tell his nemesis, ‘Joel, it’s Marty, I’m calling you from a cell phone… a real cell phone…. a personal handheld portable cell phone...’.

Cooper has recounted these events over the years, coalescing them into a sticky narrative – one that still attaches to contemporary news reports and editorials – as a compelling engineering victory story. I would like to take this particular moment, the launch of the first ever mobile phone, as the narrative starting point for my essay. I’m especially curious about what we can learn from affective narratives that circulate and even attach value to technology, perhaps even insinuating mobile phones as key tools of conquest, success and empowerment. In this context I will highlight some key figures in the cultural history of mobiles; figures who I argue have perpetuated masculine ideals of mastery and conquest-through-technology amongst audiences.

First up, there is the long-standing comic-book hero Dick Tracy, the hardboiled detective with a penchant for high-tech gadgets. The cartoon, created by Chester Gould, was first published in the Detroit Mirror in 1931 and for a period of time was even sponsored by Motorola. At one point Dick Tracy readership reached 50 million readers in over 500 newspapers (Kunzle 2017). Next, albeit in a supporting role, are the well-dressed, well-coiffed and hard-at-work men that feature in some of the first mobile marketing in the mid 1980s. These adverts reflect not only the overt gendering of mobile marketing but also augment the narratives of mobile productivity and efficiency, claiming that so-called “dead time” can be turned into productive time. Finally, there’s the character Gordon Gekko from the 1987 film Wall Street. Gekko, a Manhattan corporate raider played by Michael Douglas, stalks around plush offices speaking loudly into his DYNA T-A-C 8000X. He offers audiences an exaggerated example of the neoliberal subject -- an aggressive, empowered and mobile individual who controls and profits from the markets.

DICK TRACY

The lead character of the Dick Tracy cartoon is the physically robust good-guy detective by the same name, working in a crime-riddled city that resembles Chicago. The early plotline of the comic in 1931 centres on the kidnapping of Tracy’s girlfriend, Tess Truheart, and the murder of her father. Tracy joins the police force, rescues Tess and solves the case. The cartoon’s popularity rests on its strongman hero protagonist and gadgets as well as its colourful cast, including Flattop Jones, Diet Smith, Tess Truheart, Sparkle Plenty and Moon Maid. Gould, also a keen tinkerer, introduced the two-way wrist radio gadget to the strip in 1946. A line of Dick Tracy Two-Way Wrist Radio toys went on sale to kids with the promise of ‘getting the low-down on things the very moment they happen’. The television advert for the wrist radio, featuring a cast of young white boys, claimed to ‘keep you in constant touch with your buddies’ (available on YouTube).

A few years later in 1953 the cartoon illustrated telecasting technology to broadcast criminal line-ups to different police department locations. Soon the fiction became a reality in the New York police department (Gould O’Connell 2007). In 1954 Gould introduced the idea for an electronic telephone pick up (a pre-cursor to mobile caller ID) followed in 1956 by the floating portable TV camera, a predecessor version of the camcorder. By the end of the 1950s he created storylines in the cartoon ‘reflective of the arriving and accelerating “space race”. Themes of space travel, and high-tech crime and detection of such crime, debuted and continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s’ (Gould O’Connell 2007).

While Dick Tracy exemplifies the dynamic relationship between culture and the imagined possibilities of electronic engineering, it also illustrates how the comic came to configure a particular affective perception and bodily orientation toward the appropriation and use of mobile technology – especially as it relates to time. More specifically, I am interested in how Dick Tracy influenced the redirection of the burgeoning freedom narrative of mobile phones – from personal liberation towards superhero productivity. While initial freedom narratives were based on the idea of being mobile and connected, Tracy added a more hubristic dimension to this. In Tracy’s world, to be connected entailed conquest over others who cowered under his masterful multi-tasking. Even the Whole Earth Review writer Robert Horvitz was a fan, remarking in 1986 that Tracy’s phone-watch ‘enabled the ace crime fighter to blast away at public enemies while calling for help’.

Much like other superhero characters and their gadgets – such as Batman and his bat phone, Captain Kirk and his communicator – Dick Tracy’s wireless two-way radio watch was figured as a critical advantage to the superhero as it gave him a competitive edge over enemies. Inevitably, this sense of ‘edge’ was premised on time and multi-tasking. Tracy was able to outsmart criminals with his watch by somehow beating time. This notion that we can somehow outwit the system of time has become embedded in our relationships with technology, where technology enables us to ‘devise a unique or superior relation to … tasks that are either more enterprising or seemingly less compromised’ (Crary 2014).

The media theorist Manuel Castells argues that while it may seem that wireless communication transcends time and space, it should rather be perceived as blurring spatial contexts and time frames. ‘It induces a different kind of space – the space of flows – made of the networked places where the communication happens, and a new kind of time – timeless time – formed from the compression of time and desequencing of practices through multitasking’ (Castells 2007). Castells argues that these specific dynamics of time and space are more broadly hinged on a culture of individualism where blurring space and time form part of a set of practices around the interests, values and priorities of each individual. Rampant individualism can be seen as a defining characteristic of the 1980s, especially at the time the mobile phone was launched to consumers (1). As Jonathan Crary reminds us, ‘With the rise of neoliberalism, the marketing of the personal computer, and the dismantling of systems of social protection, the assault on everyday life assumed a new ferocity’.

MADMEN

In the wake of the mobile’s release in 1984 new marketing material targeted consumers. In a promotional video for the Motorola flip phone (available on YouTube) the desirable effects of productivity and continuous connectivity are depicted in various scenarios as mobile users transcend the so-called difficulties of everyday life. The first scene pictures a man in a casual T-shirt talking confidently into his Motorola phone, reassuring someone that, ‘I’ve got all my guys working on it right now’. The viewer catches a glimpse of construction happening in the background as the caller prepares to leave the scene on his powerboat. Also, a man dressed in a white shirt and tie appears stuck in his cabriolet car during a traffic jam, so he deftly changes his meeting time with his mobile phone.

Notably, scenes that feature women in this video are limited to either depictions of leisure or maternal care. These depictions seem to contain women in nostalgic gendered versions of themselves as carers, damsels in distress, consumers or just looking pretty. For example, a young woman answers her mobile phone while sun-tanning on the beach (later she leisurely sips a drink at a café while talking on her Motorola flip phone). In another scene a mother at a restaurant calls home to check on the children. The video jumps to a third scenario where the phone might come in handy for female users, as a woman stares at her stalled car engine as she calls for help on her Motorola – ‘Help is just a call away’!. The only African-American person featured in this video cannot remember directions and is lost in a neighbourhood, but luckily he has a Motorola phone to call for help. The video ends with a final tagline: ‘Make the most of your time’. By contrast, white American males in this video are presented as being fully in control, commanding the time and the labour of others. Problematic depictions of all other mobile users reinforce the narrative that there are some who are, at worst, in diminished positions marked by deficiency and need, who require help; and at best are confined to the realm of leisure and care activities.

I’d like to emphasise this relationship between the mobile phone and forms of affective labour, especially as it relates to the domestic sphere of kin work and care acts. With the introduction of the mobile phone these tasks can be perceived as finding a new dimension as women become perpetually connected. Notably, in this promotional video, acts of caring labour are entangled with the mobile phone, as connectivity is assumed to enable some form of autonomy from the place and time constraints of caring tasks. This illusionary narrative of freedom contradicts the very tangible reality that women who labour in capitalist economies never conform to ‘a discrete work “day” or night’ (Stabile 2012).

As Carol Stabile writes in her article ‘Magic Vaginas, The End of Men, and Working Like a Dog’, women’s working days are elastic – that is, any so-called temporal borders of leisure or work time are irrelevant in the face of the demands of emotional and physical labour such as caring for the elderly and children who don’t keep office hours. Stabile’s argument, forms part of a broader critique of the feminisation of the neoliberal subject and the gendering of affective labour. Often women’s affective tasks extend well into the night. Stabile writes, ‘For generations at least, most women have been socialized to multitask, to prioritize, to take into account the needs of others through forced collaborations’.

By the late 1980s, illusionary narratives of freedom gave way to decidedly more individualistic forms of expression (California 2017). I argue that one of the best illustrations of the status that mobile phones represented was yet to come. In 1987 the world was introduced to Gordon Gekko, the lead character in the film Wall Street, played by Michael Douglas, who won an Academy Award for best actor for this role in 1988. Gekko introduced an additional layer to the masculine mobile narrative of so-called freedom and productivity by also implicating money. Gekko, much like Dick Tracy and Cooper, seemed to evade the limitations of time and beat the competition with his DYNA T-A-C 8000X. His mantra from the film: ‘money never sleeps’.

MONEY NEVER SLEEPS

Corporate raider Gordon Gekko was one of the first film characters to use the DYNA T-A-C mobile phone not long after its public release. Set in the 1980s, film Wall Street was released only months after the stock market crash of October 1987 and critics claimed it epitomised the excess of the era and Wall Street’s obsession with power, status and making it big (Guerrera, 2010). It was the third-largest grossing film in America in its opening weekend. The film’s director, Oliver Stone, claimed that he wanted Wall Street to show the effects of ‘unbridled capitalism’. However, as the journalist Francesco Guerrera writes, ‘people viewed it [the film] differently, seeing in this muscular, vivid portrait of money and its transformative social powers a modern parable for the American dream with braces replacing bootstraps’.

Gekko quickly became a popular anti-hero, cutting a sartorially impressive figure with tailor-made suits and slicked-back hair. He became both a ‘household name and boardroom icon’ (Chang 2010). After the film’s release The New York Times even featured Gekko amongst a group of film and TV characters with enviable style: ‘Gekko - with his penchant for cuffed suit jackets and crunchy Jacquard-woven cravats – is perhaps the more compelling character … His appearance is subtle and understandable within the conventional terms of Anglo-American tailoring … The character serves as a credible model for the powerful executive who would have others follow his fashion lead’.

As a power-hungry corporate raider Gekko embodied the hubristic machismo of the finance world in the 1980s. Some of Gekko’s lines from the film, such as ‘lunch is for wimps’ and ‘greed, for lack of a better word, is good’ are still quoted in contemporary trading contexts. Guerrera described the film as ‘both a mirror and a high-water mark for the financial industry of the period’. The film chronicled ‘the dramatic change that daring corporate raiders and the availability of cheap debt had introduced into a world of gentlemen’s agreements and handshakes in a cosy, old-boys’ network’ (Guerrera, 2010).

In Wall Street a young impressionable stockbroker, Bud Fox, looks to strike it rich and under Gekko’s influence agrees to commit corporate espionage. While the young Fox is gathering information, Gekko introduces him to Manhattan’s so-called high-society perks including gentlemen’s clubs, expensive restaurants, bespoke tailoring, cocaine and ‘call girls’. Scenes in the film show offices littered with desktop computers, clunky keyboards and ticker-tape disk operating system (DOS) interfaces.

In the film the DYNA T-A-C 8000X is seemingly only reserved for Gekko, his arch-rival Larry Wildman and later, when he hits the ‘big time’, Bud Fox uses one too. In one scene Gekko calls Fox using his DYNA T-A-C while leisurely strolling on the beach at sunrise in his bathrobe. Fox is shown in his apartment hunched over his computer in the dark, clearly woken up by Gekko, croaking out the line: ‘Mr Gekko I’m there for you 110 percent’.

In his book 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (2014), Jonathan Crary offers a cogent argument for the synchronised velocity of the neoliberal subject’s daily life with the end of sleep. This synchronisation he argues, is a precursor to the ultimate market environment where both workers and enterprises are accessible around the clock.

Marketing material and media coverage of mobile phones, as discussed in the previous sections of this essay, could be seen to create a sympathetic alignment between the technology as a measure of productivity and efficiency albeit disguised in male depictions and narratives of freedom. Wall Street’s character Gordon Gekko further bolstered the narrative that leisure activities – including sleep or even time for lunch – could be filled with productive money-making tasks. Indeed, in material terms, the high price tag for the phone and high monthly call costs meant it was the reserve of the wealthy few.

The popular medium of film plays an important part in this evolving mobile narrative. Vivian Sobchack writes that as cinematic subjects, we are inscribed with ‘visual and bodily changes of situation’ that create capacity to dream and imagine. In this way, we come to know what it feels like to inhabit a certain world. Following Sobchack I argue that Wall Street affectively mobilises audiences to dream and fantasise through the male hero body and its technological prosthesis, eager to inhabit the same exclusive, hubristic and materially excessive world as Gekko. Calling on Heidegger, Sobchack views technology as a ‘bringing forth’ – a certain way of being-in-the-world. Cinema, as one such technology, alters our subjectivity – where subjectivity is understood as a socially mediated process – implicating our body in making sense of concepts such as space and time, impacting our experience of the social world (Sobchack 2004).

In implicit terms, Gekko and Wall Street further affectively orientated the early mobile adopter in a ‘mobile way of being’ in the world that included the DYNA T-A-C 8000X not only as a sign of success but also as a way of ensuring a certain fluid and male superiority outside of any temporal limits. More specifically, Gekko’s position, seemingly at the top of Wall Street, relied on his superhero ability to render situations and time as mutable, to call and ‘be’ anywhere at any time – thus insinuating the mobile phone with notions of success and ultimately money.

CHANGING HISTORY

You know, coming back in time, changing history ... that's cheating

– James T. Kirk

Star Trek: The Future Begins (2009)

As the name suggests, mobile phones are not static objects but are rather more transitive. Said differently, mobiles can be understood as events that contain various registers, modalities, transitions and orientations. So rather them close down into objects that require classification, I’m suggesting that mobiles should be approached in a way that is attuned to their affective dimensions, dynamic form and contingencies as part of politically engaging with the inherent ideologies of technology. And, indeed, they are implicated in a dynamic relationship with aspects of culture, as they shape and are shaped by culture. Our contemporary attachments to mobiles might be better analysed by looking back at the early adoption of mobile phones through certain gendered narratives and characters, such as the self-styled ‘father of the cell phone’ Martin Cooper, the hubristic characters Dick Tracy and Gordon Gekko and those featured in early advertising material.

Through characters such as Dick Tracy, Gordon Gekko and Martin Cooper mobiles are bound up with masculine notions of freedom, productivity and ultimately value. Wielding their power gadgets these hero figures perform attitudes and enact particular affective orientations that produce feelings of ontological security within the context of a more flexible, decentralised urban environment. But, most problematically, these heroic narratives represent a bias related to gender in that they assume that “everyone” experiences time and multitasking equally, refusing that the very temporal limits of familial care most often performed by women and girls can never be neatly time-stamped. The point is that narratives related to kin work are often over-written by so-called uplifting mobile narratives of ‘getting things done’. These same narratives, often reframed under the banner of “optimization, still continue to flourish while simultaneously diminishing (even negating) the demands of women’s immaterial labour.

1) Due to broadcast regulations it took almost a decade from its press launch in 1973 before Motorola could sell and market the DYNA T-A-C mobile phone to the public.

REFERENCES

California 2017. Designing Freedom exhibition. The Design Museum London.

Castells, M., Fernandez-Ardevol, M., Qiu, J. L. and Sey, A. (2007) Mobile Communication and Society: A Global Perspective. Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Chang, J. (2010) Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps: Variety.com. Available at: http://variety.com/2010/film/markets-festivals/wall-street-money-never-sleeps-1117942753/ (Accessed: 21 March 2017).

Crary, J. (2014) 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. London: Verso Books.

Gould O'Connell, J. (2007) Chester Gould: A Daughter's Biography of the Creator of Dick Tracy. Jefferson: McFarland & Company.

Guerrera, F. (2010) How ‘Wall Street’ Changed Wall Street: The Financial Times (Accessed: 25 January 2016).

Horvitz, R. (1986) 'Personal Radio', Whole Earth Review.

Kunzle, D. M. (2017) The Comics Industry: Encyclopaedia Brittanica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/art/comic-strip/The-comics-industry#ref1105977 (Accessed: 12 February 2018).

Sobchack, V. (2004) Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stabile, C. (2012) 'Magic Vaginas, The End of Men, and Working Like a Dog'. Available at: http://blog.commarts.wisc.edu/2012/11/19/magic-vaginas-the-end-of-men-and-working-like-a-dog/ 9 April 2018].